CJM Interviews Rabbi Yaakov Cohen (Part II)

As part of our ongoing series that explores the meaning of kosher cannabis, Editor-In-Chief Lissa Skitolsky (LS) spoke with Rabbi Yaakov Cohen, CEO at Whole Kosher Services in a wide-ranging interview about the laws of kashrut, Jewish history, trauma and cannabis. The first part of this interview offered an introduction to the Jewish relation to cannabis, and in this second part Rabbi Cohen and Dr. Skitolsky discuss the implications of this relationship for faith, cultivation and hope.

LS: I like the idea of Licensed Producers finding out about what’s involved in kosher certification, why it’s a concern and why it’s not even just for Jews.

Rabbi: Kosher is not only for Jews but also appeals to vegans, vegetarians, and health conscientious people who want to feel comfortable with a product that had a third set of eyes on it. Besides it is now one of the only third party certifications available for these [cannabis] products.

LS: Exactly, okay, thank you. I imagine the only reason someone wouldn’t do it is because of the expense. So how much does it cost, ballpark figure?

Rabbi: Their cost involves the travel, time and then there’s administrative stuff you have to do, you have to follow up, you have to make sure it’s all kosher. And it is a business, right? As much as it is something that is close to my heart, because it is a campaign or a crusade that I’m—that we are on—right? So yes, there is a charge, but it depends if it’s just plants it’s about $1,500 a year.

LS: Oh, that’s not bad, I expected more.

Rabbi: Now when you’re getting into developing things, you know let’s say like chocolates and gummies, then the cost gets pretty high because we have to have inspectors come out on a regular basis, 4-6 times a year. That’s costly, and it could run anywhere between $3500 to $4700, depending on where you’re located.

LS: If a blessing isn’t necessary then, do you need a Rabbi, or could you just have, like, a kosher inspector?

Rabbi: It has to be somebody who knows the laws of kashrut, who is able to look out for things, like [for example]:

“What’s in this container here?”

“Oh that’s the pig oil we spray on the plants once a month.”

“Thank you very much.”

You have to know how to look out for things, to be kind of a Rabbinical Detective. You have to make sure that every thing is kosher there and there is nothing hidden. In essence it’s food security.

LS: I love that, food security. I love the whole sensibility of being-kosher, of setting limits or rules for how we treat and engage with other species. I’m really interested in how being-kosher connects with Jewish philosophy or our sensibility towards nature.

Since I’ve started growing cannabis, I’ve become a lot more interested in the agricultural laws [of kashrut], that people are less familiar with. As a whole, these rules indicate that we shouldn’t ever act like we “own” the land, or we “own” plants, or we’re their masters. We have to remind ourselves a lot that these are also other species and this is also Hashem.

Rabbi: Yes, everything, it’s all God’s.

LS: This is something I’m exploring in Cannabis Jew Magazine, in terms of how we cultivate cannabis and what “kosher cannabis” means in this larger sense. Because even though [as currently defined] kosher cannabis has nothing to do with how it’s cultivated, from my perspective, as a grower, I see cannabis cultivated in living soil—where it exercises agency, develops all of its systems in a community that helps it thrive—as [respecting] a kosher sensibility. And as I mentioned, insects on the flower tend to be a bigger problem for cannabis grown hydroponically.

Rabbi: I’m amazed; so this guy puts worms in the soil and that results in less microbial matter on the flower?

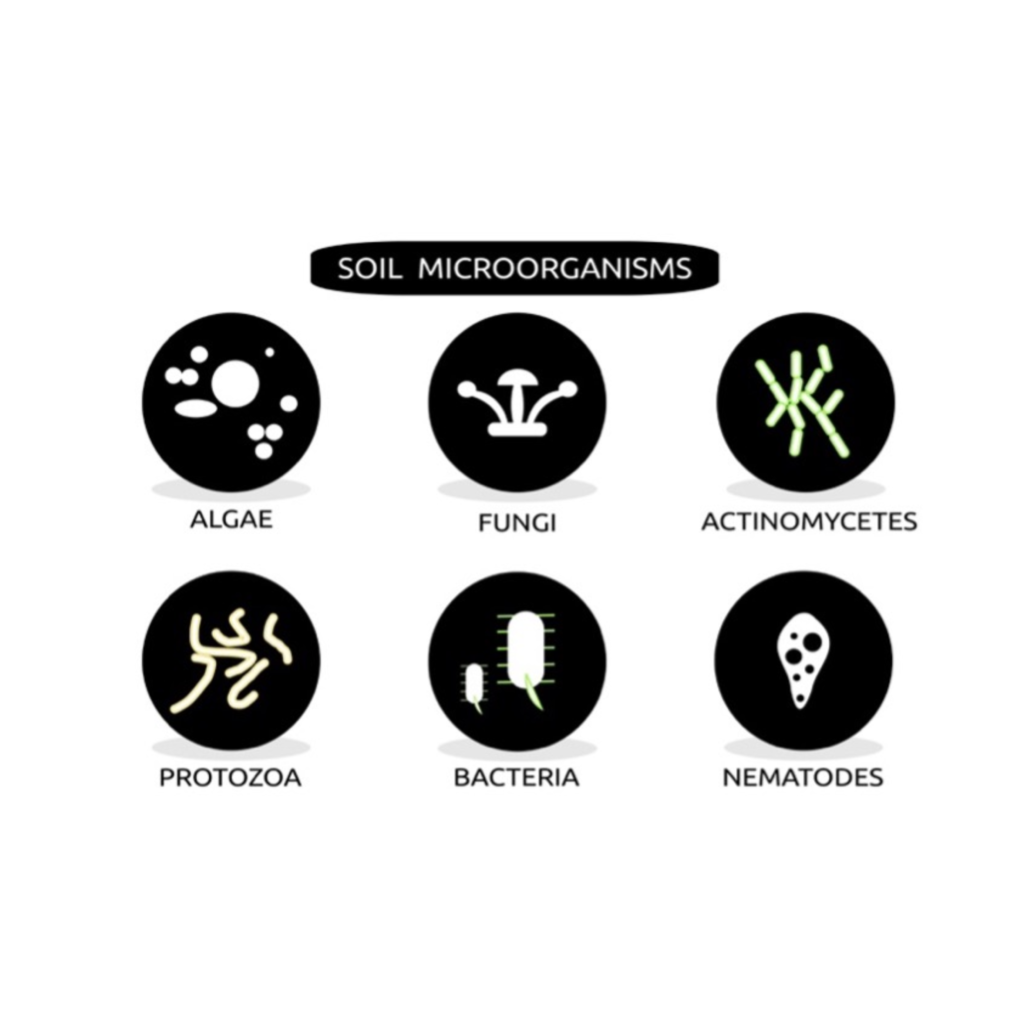

LS: Plants develop their immune, respiratory, digestive systems through mutually beneficial interactions with microorganisms in the soil. Soil is like a microbial community with all of these different species working together to optimize each other’s health.

So hydroponics is a totally different way of cultivating cannabis, right? When you cultivate outside of soil, which is any hydroponic method, you’re making it impossible for cannabis, as a living thing, to take an active role in its own growth and development.

Rabbi: It’s probably drek cannabis. I’m sorry to say it. When they grow lettuce hydroponically here, and I’m looking at this lettuce, I’m thinking “how nutritious is this really?”

LS: Exactly. I think that there’s something [significant] to thinking about what is kosher in terms of how it’s cultivated.

Rabbi: Believe it or not, according to kosher law, there is no real kosher issue in terms of how it’s cultivated except for the blending of different species close together. Besides that we don’t care what you put in the soil. However bugs can be an issue since bugs do eat plants, so plants need to be inspected before eating.

LS: Check it out: bugs that eat plants and harm them only go after plants that are vulnerable and sick.

Rabbi: I’ve heard that before but I never knew that was proven. “They say that “organic produce is strong and resists the bugs naturally.” Some people have told me it’s not true. Many rabbis claim to have proven it to be not true. But I’m open to be proven wrong.

LS: It’s just because the plant can’t actually go through its entire life cycle, or develop a working immune system or digestive system, or modify its uptake of nutrients—outside of soil. When cannabis is grown outside of soil, she can’t do any of that, but all of that contributes to her health and wellbeing. People don’t really think about plants as living beings that have life cycles and can thrive, and [consider] that they thrive in certain environments.

Rabbi: In Judaism and Kabbalah everything has life, even rocks, everything has a vibration. But we’ve lost touch with that.

LS: I’m really happy to hear you say that, because I don’t mean to pretend to be a rabbi, but I have a critique of the rabbinical certification of hydroponics as being kosher, which rested on a rabbi’s opinion that there’s nothing important about soil in itself, it’s just a container.

Rabbi: Yes and No. Yes and No. laughter. The way you describe it, c’mon man, it’s Mother Earth—what are you, crazy? But everybody’s more worried about the bug-free lettuce than they are worried about Mother Earth. I think over time the Jewish people have lost that connection to mother earth. G-d willing we will get back to that.

LS: I also just wanted to tell you something, I think it’s going to warm your heart and kind of bring everything together. When I talk to Jewish doctors and researchers in cannabis, they all have the exact same story⏤almost all of them—which is that they weren’t interested in cannabis until a family member or friend got sick, and cannabis helped them enormously. So they pivoted to cannabis—to medical cannabis in particular—and now they’re obsessed with increasing access as much as possible.

To me, it’s just so beautiful in terms of how Jewish it is: “if this plant helps reduce pain and suffering, then of course we’re going to be open to it.”

Rabbi: The interesting thing, you know, we look at the world as always being run by Divine Providence, and everything has its time and place.

And for some reason cannabis has come out recently, right? I mean it’s been around for thousands of years but now in terms of, let’s say, the legality of it, to permitting it and the research—it’s time. It’s time for that stone that everybody cast away by the builders to become the corner stone.

The corner herb. And it has to take its place in creation in terms of healing humanity.

LS: So many Jews can’t be wrong.

Rabbi: Well you know, there’s that stigma; the Torah really doesn’t have a concept of recreation.

LS: This is not recreation, it’s all medicine.

Rabbi: Yes, it’s purposeful living, and everybody is worried about it getting out of that category of purposeful living, and time wasting, and not producing in life. So we don’t call it recreational, it’s called now “adult use.” That was my argument with the Rabbis, because I was giving kosher certification to gummies, fruit slabs and they’re saying “recreational is forbidden, recreational is forbidden.”

I said: “who says something edible can’t be used for medicine?” and that was it, that was the end of the conversation. They didn’t have any answer for that, because it’s easier for an old lady to take a gummy who needs to sleep. She doesn’t want to smoke, she wants to take a gummy. It’s easy.

I’m still trying to wrap my head around why there’s so many Jews involved in cannabis. The main answer that comes to my mind is the innate part of the Jewish soul that seeks to fix the world. Heal the world. That’s why so many Jews become doctors or therapists. But I think there is a deeper explanation that I can’t seem to touch on.

LS: The “why” is important to think about, because we don’t want other people to answer that question for us.

Rabbi Yaakov Cohen was born and raised in California where he attended Cal State University, Northridge, where he studied philosophy and psychology. He went on to study at a number of leading yeshivot in Jerusalem where he received his Rabbinic ordination.

Rabbi Cohen has been involved in outreach in Texas for the past 20 years and continues to give classes online for TORCH of Houston. He learned Kabbalah under one of the great Kabbalists of Jerusalem, his father-in-law Rabbi Shabtai Teicher OB”M. Rabbi Cohen has taught seminars and lectures of Kabbalah, mysticism and Chassidic thought in both America and Israel and now currently resides with his family in Ramat Beit Shemesh, Israel.

Here are a few links to some of Rabbi Cohen’s inspiring lectures on Jewish ethics and Kabbalah: